This week’s post is a conversation between Michelle Scully and Elizabeth Nawrocki about community, action, climate change, and hope. We recommend listening to the audio recording - you can imagine yourself joining us and our lavender lattes in the corner of Werner Books while having this conversation. A transcript is also below.

If you are a woman in your 20s or early 30s and would like to immerse yourself in the Erie Benedictine life and be a part of similar conversations and action throughout the next year, check out the Benedictine Peacemakers Monastic Immersion - priority deadline for applications is February 28, though we will accept applicants through April 30.

Elizabeth splits her time between Erie, PA and Big Laurel Learning Center in Mingo County, WV. In November 2024 she was at Big Laurel when a fire broke out during an unprecedented regional drought. Alongside of her neighbors, she spent 10 hours a day breaking fire breaks and moving brush around as the community worked together to protect the people and buildings in the area.

More recently, in parts of West Virginia and Kentucky, snow melt and heavy rain storms caused devastating flooding to the region. Elizabeth notes that “everyone talks about this flood in 1977 that, changed the landscape of everything, and it's kind of like a point in time- a marker that everyone talks about, like, ‘well, after the flood - after 1977…” So that time the Tug Fork River crested at 54 feet, and this most recent flood it was 51 feet. So again, in this same lifetime – landscape changing, community altering.”

Our conversation meandered through a field of big questions that don’t have single answers – how do you take the urgency and collaboration of a community response to disaster and shift that energy also to the “before” – to organizing and collaborating in meaningful ways? Do we know our neighbors? How does that answer vary by generation, by location, by circumstance? What does that mean for our local communities if we don’t even know each other?

In her book How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, Jenny Odell urges “let’s not forget that, in a time of increasing climate-related events, those who help you will likely not be your Twitter followers, they will be your neighbors.” How do we build strong geographic community, not only communities through online networks of those we think like?

The following is a piece within this conversation:

Michelle: When we have conversations about community and relationships that are on these very small levels, I guess, in a lot of ways- on personal levels of ‘who is my neighbor, right?’ And loving the people directly around you and coming in support of communities in these disasters and such… is there potential to transform that to a larger scale or is that something that is inherently small? And where's the hope or hopelessness in that when you're thinking of governmental institutions? And is there, I don't know, any hope of things on a larger scale that feels very corrupt and not in any way community-oriented?

Elizabeth: Yeah. I think one thread I would pull from that this is where that word that we both have been thinking about -bioregionalism - could be. I don't know if it's like a philosophy of place that you would call it or something like a rootedness or a groundedness of specific place on this Earth in this system- which does happen to be a political system, a municipal system that may or may not be meeting our needs on whatever, whatever level, whatever scale. I am wondering recently - maybe have been convinced for a long time too- but I think it does have to start there. Not that you need a crisis like a flood to really anchor you in that kind of community, but I think that sharing space with someone and sharing life is going to be a prerequisite to building these kinds of strong bonds. And the way that looks in Kermit, West Virginia, in the hollers of Mingo County is going to look different than how it looks in Erie, Pennsylvania, in this municipality here.

And that’s where it's like, okay, so this bioregion of the Tug Fork River - the organizing can start there on that level and community building can start there on that level. And then in Erie, similar things can happen. That is the level of my hope for change - institutional and policy. I personally, for a few years at this point, I've just been realizing oh yeah, federal level things - like I realize the optics and all of that is important. And yes, I realize that these presidential elections do have consequences for people in real life – and I don't think voting any particular person into that position is going to change that.

It's not that I've abandoned hope in that realm of things, but I do think that it has been like really scaled down for me. And then I think when we are within these bioregions – it’s not to say that like, hey, we're building walls around ourselves and be like a fortress. Rather, we know what we need. We know there still is interaction between all of these spaces and there has to be interaction between all of those spaces. And honestly, I feel like that is what this flood experience in Mingo County is kind of activating in me right now. I am part of that community. I'm not there right now. It’s weird to be seeing it online and like be talking to everyone like daily, hourly about what's going on down there. I think where we can recognize like, “oh shit. Okay. So our attention needs to be here right now. And we can organize our money and our people and our power for this specific thing right now and address that and help build that back up.”

Michelle: It's the principle of subsidiarity, right? Like you focus on the smallest level first. And that's not, that's not to go how JD Vance kind of perverted things into this “America first” interpretation of how to love people.1 A type interpretation of how to love people, not that you have to keep your love small in a way that doesn't allow you to love other people, but instead that you start your love and your action and your response and your community building with the communities that are directly in front of you because that's where your relationships are, and that's where you're invested in and that's where you can start and that naturally grows, right? If you're coming from a Christian perspective with this idea that “love begets love” and that love is something that is life-giving and a creative –

Both Michelle and Elizabeth: a creative force

Michelle: - right? And so like, of course, starting with the communities that are closest to you will allow that to grow if everyone begins there. And the cynicism is not as much, I think, when you're working in the communities close rather than like the federal level where you feel like you're yelling at the sky. Or showing up to the federal building in downtown Erie and there's no staffers in any senators' offices, for example.

Elizabeth: Yeah, I mean, I even think of the idea of a loving-kindness meditation that starts with one person and then you see one person that you really love, admire, adore and then the practice is like, okay, now can you expand that? Like expand that to more people, expand that to more people, to more people. That’s how that practice goes too.

Michelle: Right, not like “I need to keep love small.”

Elizabeth: I've been thinking particularly too about how marginalized people and vulnerable populations are the ones who are going to disproportionately see the effects of climate change. And I think about my friends who I know who live in a trailer right on the banks of Marrowbone Creek, in a lot of need already, baseline a lot of need, baseline a lot of trauma in that family and their life and their experience. A few years ago when the creek flooded a little bit, their whole trailer got flooded. So then the effects of that - you know, they were displaced for a while. And then when they did return, like that trailer is probably full of crazy mold that is affecting their health, that is affecting everything else. And then again - so that family who's already suffering so much, once again is right now displaced and yeah, don't know when they can return, if they can return, what that's going to look like.

Michelle: When there's no structure to hold people when climate change [destroys], right? The fires in LA and just the vast communities that that has wiped out. And now the ban on ice raids in places like disaster relief areas has been lifted. So in LA, you have people not wanting to go to the disaster relief areas because that is a vulnerable place now.

Elizabeth: I know the people doing work in Kermit right now in crisis response mode, like sending the money, supporting them as I can. And this being separate up here, it's kind of given me space to think about like some of the bigger things and some of the questions that I think we'll have to address after this - how do we move forward? Like, what is it that we're building or shifting to make sure that people don't suffer in this way again, when this happens again, because it will happen again.

I don't think that this is like, well, “this is the sin of colonial extractivism that is like coming for a reckoning right now” - we can talk about that later - but like, this is going to come, people are going to be affected. How do we then build our communities and leverage the things that we have learned from these experiences to redirect that? And maybe that's where, maybe that's the space when we were talking about building community as crisis response versus, “is that something we can do beforehand?” Kind of relates to this random thought I've been having recently in this, just a quick little [art piece] I threw together – “what if this is an alarm and not the end?” How does that shift things when we look at them as a warning or like “hey, this is what's gonna happen when things are set up like this.”

Michelle: I was just - on my drive over here this morning- I am listening to Rachel Held Evans' book Searching for Sunday. It was playing in the car and there was this quote where she said that - well she was talking about institutions overall and death - and she said, “empires are afraid of death, gardeners are not.” Because are you cultivating things that will grow or are you holding tight to something that can collapse?

Elizabeth: Oh wow. All of the gardener imagery that I want to go down now and talk about!

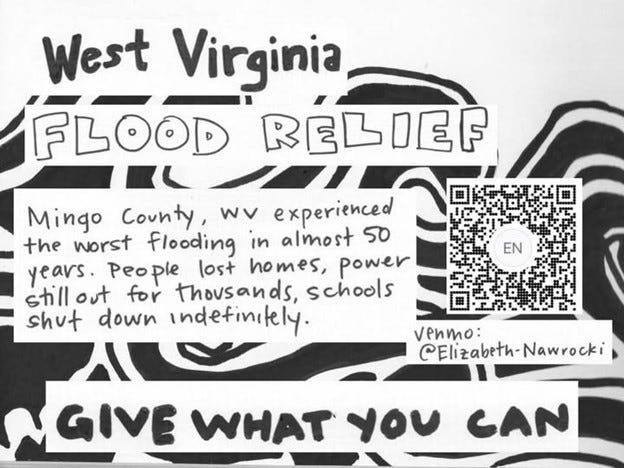

If you’d like to financially contribute to a mutual aid fund for those in Mingo County, WV you can do so through Elizabeth’s Venmo below: